February de 2011

DIALOGS AND IDENTITIES

Renata Felinto

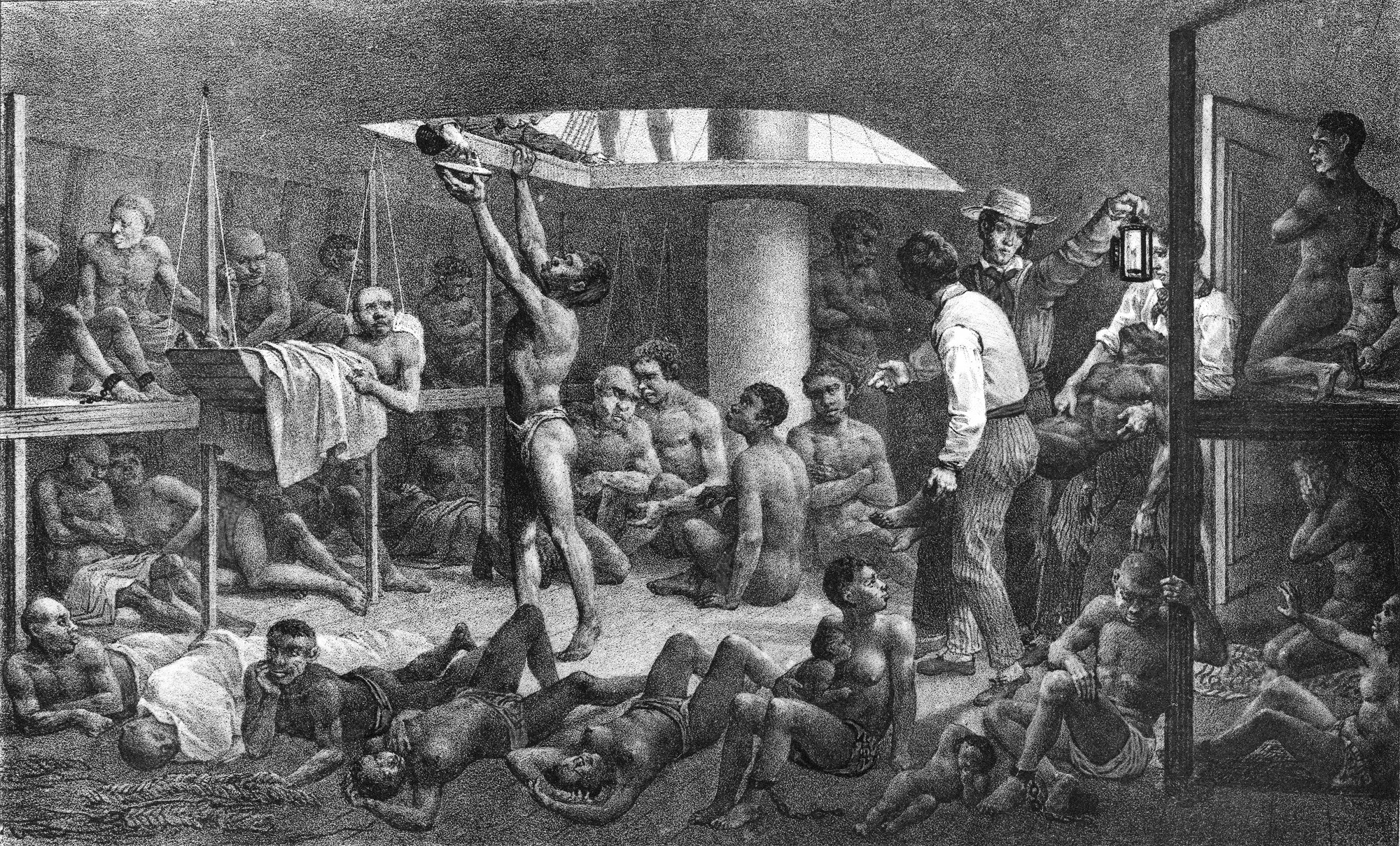

cover Negros no navio

Rugendas

To make things easier to the analysis of the representation of the black man in the plastic Brazilian arts along the last five centuries, we will chronologically divide this study in three different moments: documentary (what includes the production carried out during the centuries XVII, XVIII and XIX), social (what comprises the first half of the century XX) and personal (what includes the production of the end of the century XX up to the current moment).

The documental moment includes more detailed national peculiarities such as geography, fauna, flora, population, manners and customs. Significant part of the production of this period was made by foreign artists that arrived in Brazil, generally contracted, with the objective of making works of documental types and that were related to specific aspects of the new land reality.

In 1637, the Holland artists Frans Post (1612-1680) and Albert Eckhout (1610-1666), arrived in Pernambuco contracted by Prince Mauritius of Nassau. Post documented the ports, fortifications and the exuberant Brazilian scenery, representing in his works the black man as a supporting actor, an element of the composition of his paintings, as well as the trees or the animals.

On the other hand, Eckhout painted the fauna, flora and the curious human types producing a set of eight paintings that show human types found in Brazil, and two of them are representations of black men: Man Negro and Black Woman (1641), where black men appear like inhabitants of Central Africa and not as slaves in Brazil, a detail that checks to the paintings allegorical tone.

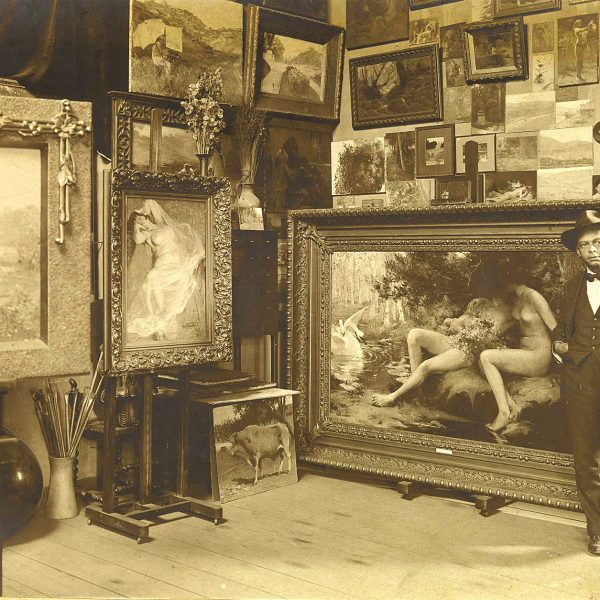

Albert Eckhout

Mulher africana

Óleo sobre tela

1641

In the XVIII century, Carlos Julião (1740-1811), an Italian soldier that served the Portuguese Crown, registered in his watercolors the regions of Bahia, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, anticipating the type of common representation in the XIX century that focused the daily life of cities and towns.

In the baroque, final period of the XVIII century and part of the XIX century, the Portuguese’s son Manoel da Costa Athayde (1762-1830) immortalized the black woman, mixed race, in the ceiling of the Church of Saint Francisco de Assis, in Ouro Preto (MG), in the figure of Nossa Senhora da Porciúncula.

In 1816, the artists of the Artistic French Mission arrived in Brazil, who consolidated here the esthetic European paradigms that would be bases of the Brazilian production and so on. Among them, one that has gained prominence was Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768-1848) that registered the daily life of the capital on its recent Empire, the city of the Rio de Janeiro. In his works, the situations of slave labor include also the daily relations between liege and captives, and the figure of the black man assumes unique importance. Another important traveler-artist of this period was the German Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802-1858), who arrived in Brazil in 1822 contracted by the Expedition Langsdorff. In his watercolors and lithographies black man also appears in a sort of chronicle of the city of the Rio de Janeiro, in a distanced way in situations of labor and punishment.

However, it’s by the end of the XIX century that appeared the first black artists who opened way for other black men also artists and that represented themselves and their culture. One of them was the native of Rio de Janeiro Artur Timotheo da Costa (1882-1922). Graduated from the Imperial Academy of Beautiful Arts, on his paintings the black face is the beauty to be studied in its lines, forms and colors, transmitting gentleness and delicacy through its stroke, as seen for example, in the work Boy’s Portait (Retrato de menino).

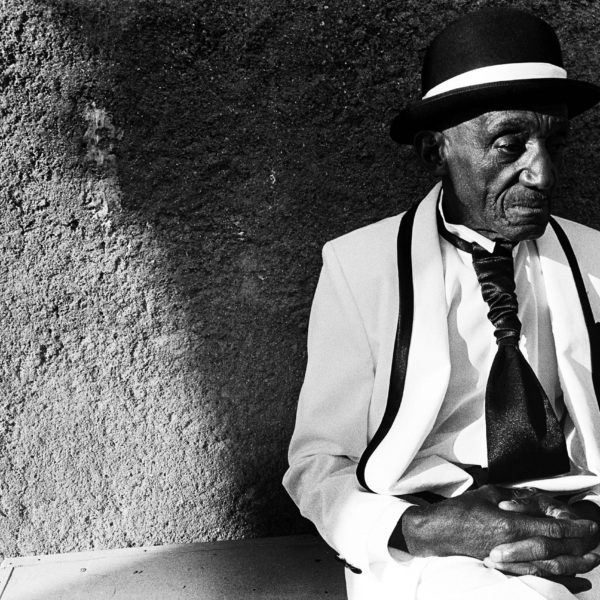

*Arthur Timotheo da Costa

Retrato de menino

Óleo sobre tela

s.d.

Still at the end of the XIX century black man was also widely registered through the photographic language, which had great prestige at that time. Among the photographers of the period it can be mentioned the Portuguese Christiano Junior (1832-1902), who mounted scenes in his photographic studio in which the black men were representing slaves of profit; and the native of Rio de Janeiro Militão Augusto de Azevedo (1840-1905), who took photographies of black families in Sao Paulo worn in clothes of that time to watch the masses on the Church Our Lady of Rosary, frequented by that population.

At the end of the XIX century and beginning of the XX, the representations of black men in the Plastic Arts characterized the successful moment as social, ‘cause in the modernist period to black man figure were attributed some Brazilian aspects. At this moment, there are two more visible slopes of representation: the black man harnessed to the slavish past and / or as an individual.

Zezé Botelho Egas[1] and the native of Rio de Janeiro Pedro Bruno (1888-1949) make part of the first group, with works that, even on a moment of exaltation of the black man figure, represent him in situations of torture or slave labor.

The Italo-Brazilian Alfredo Volpi (1896-1988), the man from Sao Paulo Candido Portinari (1903-1962) and the guy from Lithuania Lasar Segall (1891-1957), three of the biggest modernist artists, painted the black man as the individual, in different situations that exalted his history, culture, beauty, social situation and individuality.

After the initial modernist change of direction, many black artists without academic formation advance on the artistic national and international stage taking for themselves the commission of representing their cultural inheritances and way of living, transposing barriers imposed by the academy through its originality, vivacity and creativity. As seen on works of the natives of Rio de Janeiro Heitor dos Prazeres (1898-1966) and Sérgio Vidal (1945), and of the one from Bahia Agnaldo Manuel dos Santos (1926-1962).

From 1990 on submerge from peripheral studios the representations pointed how that of personal character, which presents sensitive points of view and perception about African diaspora and its continuations, as it’s possible to see on Eustáquio Neves’ work (1955) – a man from Minas Gerais and Rosana Paulino (1967) – a woman from Sao Paulo.

As we can observe, the representation of the black man in the Brazilian Plastic Arts suffered important transformations along the centuries. If on the first images black man was represented allegorically seen by foreign eyes, now it’s the black men himself who gives the tone of this representation, assuming his own speeches, being, simultaneously, the creator and creation of his personal histories and of his ancestors.

+

NOTA DE RODAPÉ

*[1] Dados biográficos desconhecidos.

COMPLEMENTARY READING

A travessia da kalunga grande: três séculos de imagens sobre o negro no Brasil (1637-1899)

Carlos Eugênio Marcondes Moura

Edusp

São Paulo, 2000

Pintores negros do oitocentos

José Teixeira Leite

MWM-IFK

São Paulo, 1988

A Mão Afro-Brasileira – Significado da contribuição artística e histórica

Imprensa Oficial do Estado de SP e Museu Afro Brasil (2ª. edição)

2010

ITAÚ CULTURAL

itaucultural.org.br