March de 2014

GERMAINE ACOGNY: WRITINGS FROM A BODY IN REAL TIMES

Luciane Ramos-Silva.

article Luciane Ramos-Silva

photos Guto Muniz

In the fall of 2004 the city of São Paulo had contact with Fagaala, a choreography that discussed the human tragedy of the Rwandan genocide. It was the first time that I witnessed, in the skin of my eyes, the creation and meeting of art, politics and rapture of one of the most important choreographers and dancers of our time: Germaine Acogny. That was not her first time in Brazil, but that day, the saying “dancing is a way of being in the world”, teaching from the African experience in Brazil, became concrete for me, in flesh and movement.

The path of the Franco- Senegalese, originally from Benin, dancer, choreographer and teacher, makes us think on how tradition, modernity and identities dance, on self awareness and on the reinvention of the africanity in contemporary world. Her teaching and art put together very important ideas and beliefs, discussing the awareness of the body and the world.

Germaine, na Ecole des Sables, no Senegal, escola que fundou em 1998. (photo Luciane Ramos-Silva/2010)

Besides her international recognition for over 50 years teaching and dancing in France, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, the United States, China, Brazil, Madagascar, Burkina Faso, in places such as the Theatre de la Ville, in Paris, or in events such as the Lyon Dance Biennale and the Melbourne Festival, Germaine writes her story from a very different point of view from the common thinking when talking about Africa – the African man is not a victim, a primitive and passive person. As a very attentive citizen-artist, she discusses, criticizes and reflects on the ground beneath her feet, and shows what is universal from African corporality and symbology.

ROOTS AND BRANCHES – MUDRA AFRIQUE PROJECT

Born in 1944 in Benin, Germaine moves to Senegal when she was about five years old. As a youngster, she moves to France where she attended physical education. When she returns to Senegal, she deepens her work at joining to it the wisdom of the body learned from her ancestors, as well as the fundamental elements of African dance – music connected to movement, while and space; gesture connected to elements of nature.

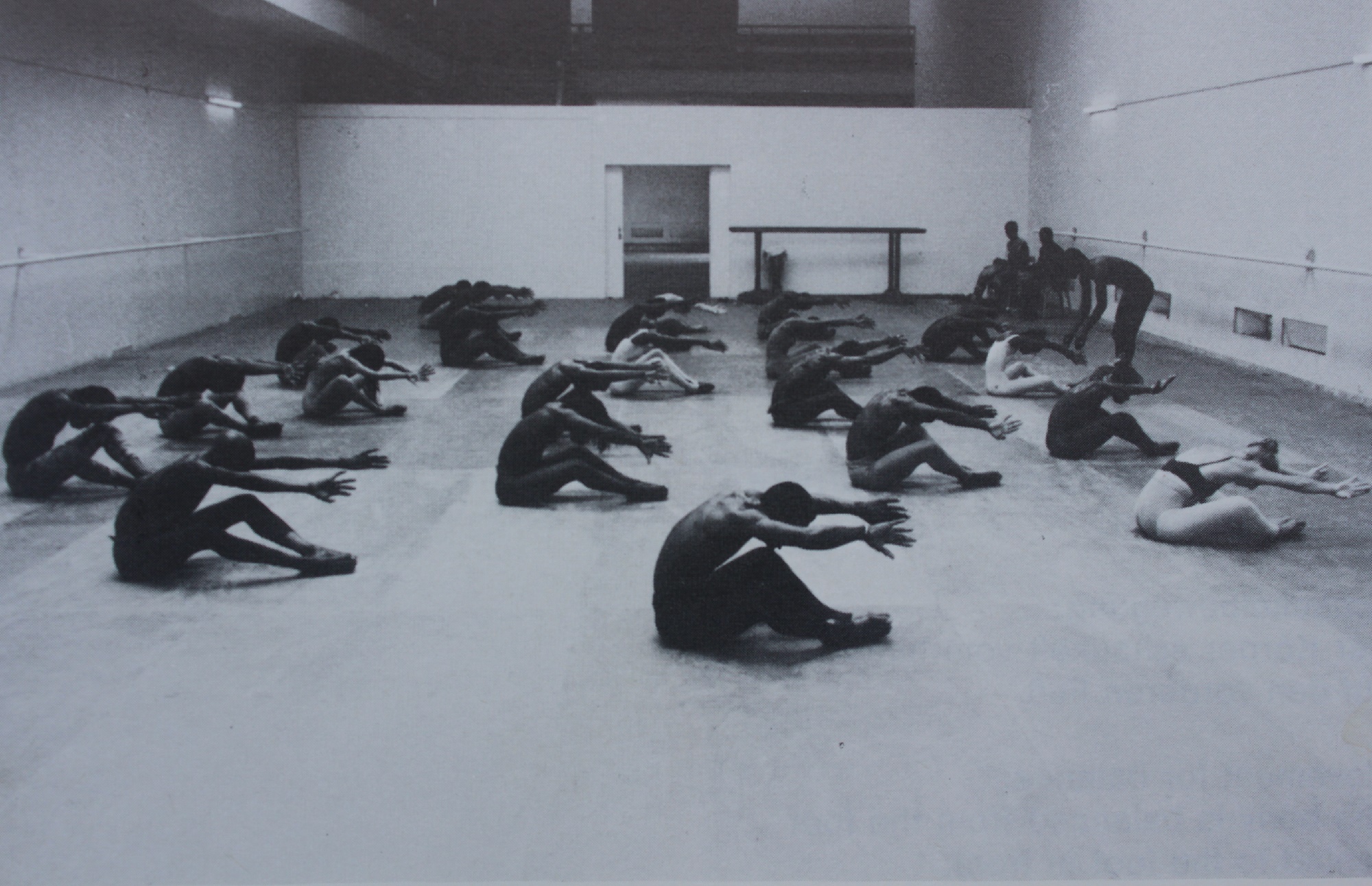

In the mid 70s, Leopold Sedar Senghor (1906-2001), the first president of independent Senegal, invites Maurice Béjart (1927-2007) founder of Mudra, an international dance school in Brussels, Belgium, to head the project of a Pan-African dance school, the Mudra Afrique, a program that would strengthen a wider idea of cultural policy, by thinking arts as an important side of a Nation-State plan, based on the idea that African political unity was associated with the awareness of cultural identities of black civilizations – a policy of openness, as Senghor believed in the universality that these expressions could acquire, a controversial thesis that would produce a series of consequences in the movement that he helped to create – the Blackness- and later thoughts on the position of African societies in the modern world.

Maurice Béjart meets Germaine through Senghor, and invites her to be the artistic director of the school – an interdisciplinary and intercultural environment that would join artists from across the African continent.

Opened in 1977 in Dakar, the Mudra Afrique aimed to develop an African dance that could be experienced “by all men of all civilizations”, because it was expected to be universal. The training was based on African dance and classical ballet, among other dance languages.

The school received partners like the Cuban choreographer Jorge Lefebre (1936-1990), who danced in the Katherine Dunham Company, Judith Jamison (1943), north American dancer and choreographer, artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and the prestigious Senegalese musician Doudou Ndiaye Rose, responsible for the musical education. By lack of funding and institutional support, the school closed in 1982, but it promoted some other experiments in the bodies of artists who had studied there, such as Irene Tassembedo (Burkina Faso), Longa Fo Yeye Oto (Congo) and, above all, Germaine Acogny, with her project for an international dance school that would become reality years later.

DANCE COMES FROM THE SAND

When Mudra Afrique closed, Germaine worked on projects which aimed the creation of an international center for traditional and contemporary African dances and in 1998 she founded the École des Sables (Sand School) in Toubab Dialaw, in Senegal, a space for professional education, an environment for exchanging experiences between dancers from Africa and from the world. Several classes, internships and immersion programs are offered in the school, focusing on African dances.

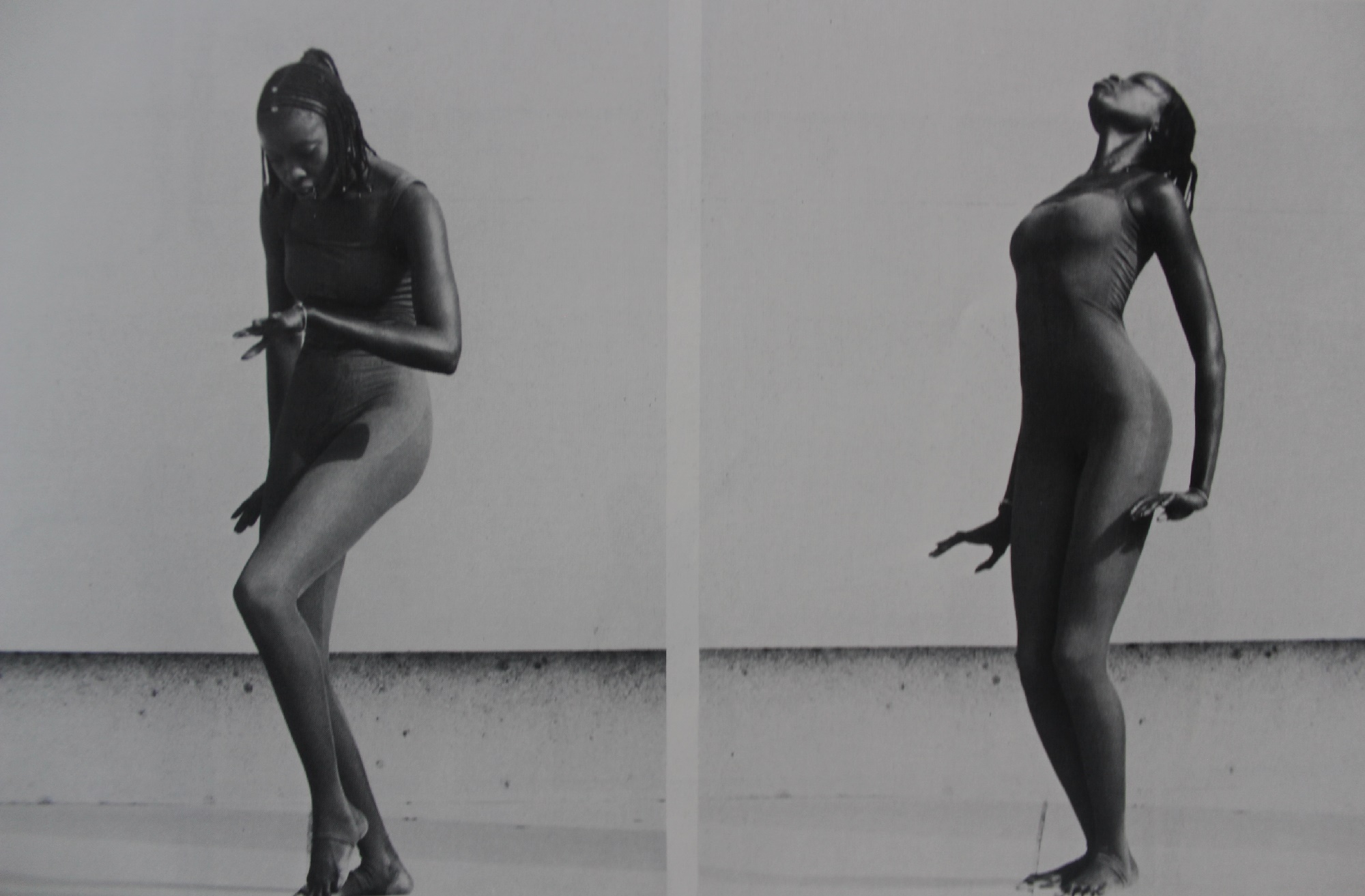

One of the training programs offered, Transmission, is specifically designed for pedagogy and practice training on Germaine Acogny´s modern African dance technique – which brings together the essence of West African traditional dances and European dances, such as the ballet. The word « Step » in classical ballet language, is named “movement” in Germaine´s technique, and it is not by chance that her teaching process is based on African culture images and symbolic elements: the Baobá tree, the Ashanti doll, the palm tree, the dromedary, among other references. Germaine connects the symbolic with the body structure focusing on the energy connected to movement , on rooting the feet on the ground, on the awareness of the core and the spine, the basis of her pedagogy. Beyond the systematization of the movements of African dances, which is in her – African Dance (1980) book, a major contribution of her thought is the evidence that, on the opposite of common thinking, African dances are not innate, but they are the result of long and constant learning and discipline.

“If African dance creation is an African domain, it is open to everyone. Non-African students widen their universe learning our method, our movements, as well as an African student learns classical or modern dance steps”.

The École de Sable funds comes primarily from foreign institutions. Germaine persists, with her husband and partner in the school founding, Helmut Vogt, and her son, Patrick Acogny, whose doctoral thesis discussed Acogny Technique and the genesis of intercultural corporalities. They are constantly attempting to receive support from the Government and private African institutions that can enable the training of young Senegalese and African dancers in general, considering that training is the core of the school project – a virtue and a need, since we know that, such as in other fields, the “brain drain” of the continent also affects the world of dance. Dancers frequently move to France, Italy, Spain, Czech Republic, the United States and other countries, aiming better structure and living conditions, even if those desires are often sandcastles. The extract of the African Dance book quoted above, shows us the openness of black cultures, very interested in receiving foreign influences and reworking them. Thinking more carefully about Brazil, a question could be asked: Are dance artists in their multiple areas of expertise, willing to such displacement, to such openness?

JANT-BI: THE CONTEMPORARY WITH ANCESTRAL ROOTS

One of the biggest dilemmas of African societies and the Diaspora is the recognition of their contribution to history and contemporary experience. Along its path, Jant-Bi Company (which means Sun in wolof, one of the languages spoken in Senegal) stimulated artistic creations that broke stereotypes about African cultures, lighting current wealth and dilemmas without, however, denying what might be part of their vernacular knowledge. The Congolese master Longa Fo said years ago at a seminar in the city of Uberlândia: “Tradition is not static, it evolves”.

Founded in 1998, together with the École de Sables, Jant-Bi Company has a collection of choreographies already danced in different parts of the world: Le coq est mort, choreographed by the German Suzanne Linke (1999); Fagaala (2003) in collaboration with the Japanese choreographer Kota Yamazaki and stimulated by Boubacar Boris Diop´s book Murambi, The Book of Bones ; Waxtaan (2007) a criticism of the African heads of State and an appeal to the transforming power of citizenship of the continent; Opera du Sahel (2007), Les écailles de la mémoire (2007), a partnership with the powerful New York- based Urban Bush Women Dance Company are artistic works that, in their plurality, put on stage powerful bodies both in dance and speech, because they bring up deeper issues of the societies where they come from and their relationship with the world.

When she puts African and western dances on the same level of importance, Germaine shows a more horizontal coexistence between Africa and the West.

SONGOOK YAAKAR – THE EXPERIENCE FACING THE HOPE

Book African Dance (Danse Africaine/ Afrikanischer Tanz), Germaine Acogny, 1980.

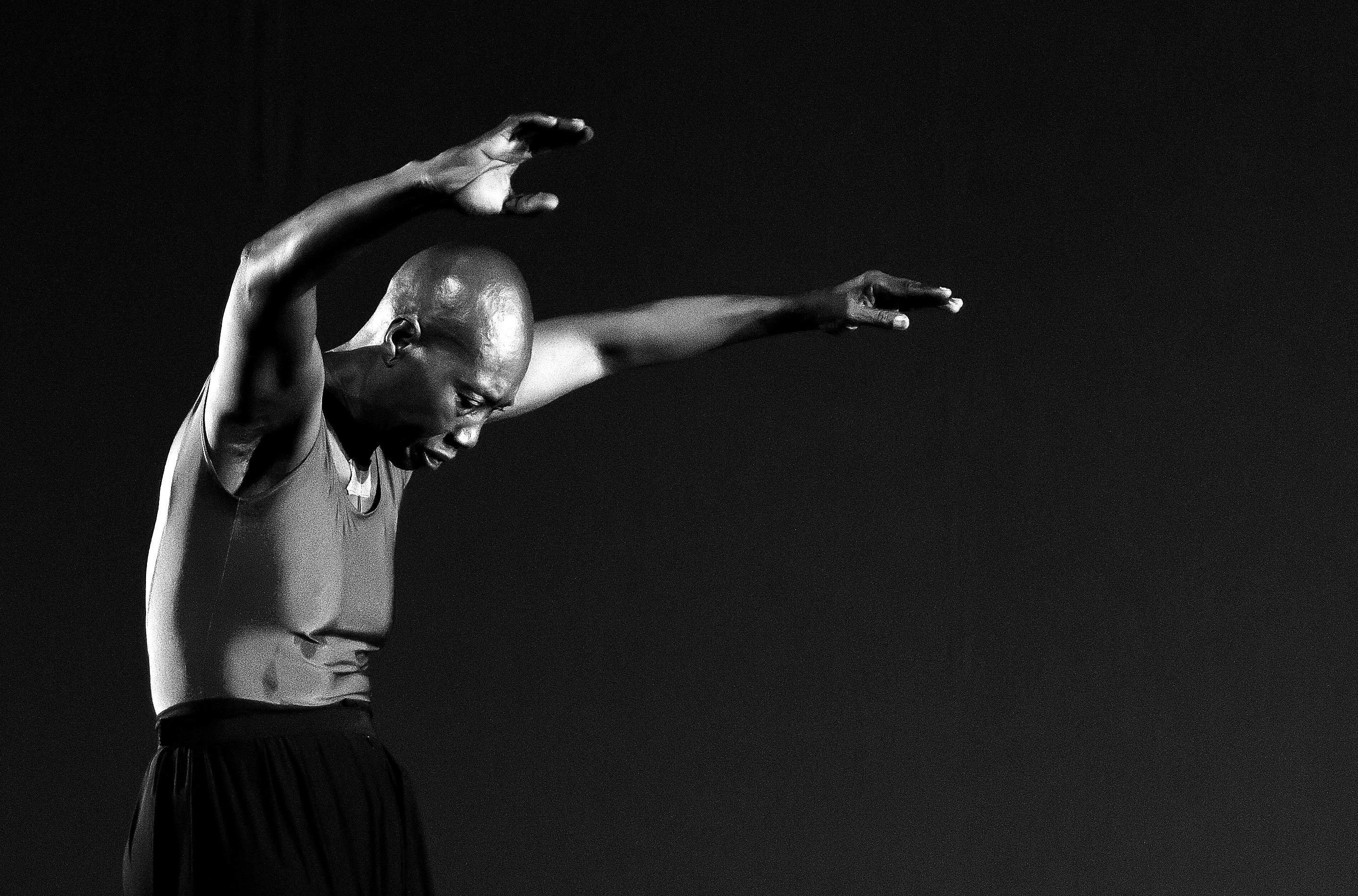

The body of the “African modern dance mother” also dances. Her vivacity and power on stage were developed on the solo pieces Sahel (1987), Ye´Ou (1988), Tchourai (2001)e Songook Yaakaar (2010).

Contrary to a very current tendency among dance professionals who, at reaching a certain age are discarded by the market, Germaine does not stop. As a living proof of what she defends as a benefit of African dances – the fact that they do not deform or suppress the body – and about to turn 70, she still teaches and dances with energy. Her solo piece Songook Yaakaar, performed in 2012, in the SESC Dance Biennale, strongly shows its literal meaning – Confronting hope. She discusses with irony the Western fantasies on Africans and satirizes a number of assumptions of the “global community”, questioning the processes of migration, exile and diaspora.

In the senses produced by her dance, poetry and politics are put together, by using film projections and texts spoken in a plaisanterie way, a social practice that exists in several cultural universes of West Africa which authorizes the members of the same family, even distant cousins ??or members of close ethnicities, to mock and make fun with each other. This verbal clash works as a means of cleaning tensions through laughter. Germaine brings this element to the stage and updates it, as in the scene where, in derision, she revisits remarkable contemporary moments and cites the unfortunate speech by former France President Nicolas Sarkozy, on the role of Africa in the world history: “To that man who said [that the tragedy of Africa is that the African has never really entered into history], I say: You are right sir, since the first man to enter into history was a woman, three million years ago – Lucy, the mother of mankind, celebrated by the Beatles”.

“àquele senhor que disse [que o drama da África é que o homem africano ainda não entrou suficientemente na história], eu respondo: Você tem razão senhor, desde que o primeiro homem a entrar na história foi uma mulher, há três milhões de anos -, Lucy, a mãe da humanidade, celebrada pelos Beatles”.

Bringing her ironies to the Brazilian context she invited the audience to celebrate the independence of the country, since it was September 7th. Her plaisanterie fit it like a glove not only because it was fun, but also to call the attention to our common experience of colonization.

Germaine Acogny´s dance is connected to her story, which is constantly renewed by a very wise notion of ancestry as a springboard for the modern experience. She speaks of Africa, but also of our humanities – which are universal.

THE SEAS WE CHOOSE TO SAIL

In 1995 Germaine was invited to choreograph for the Balé da Cidade São Paulo, an important brazilian dance company. It was the celebration of three hundred years of Zumbi dos Palmares and the company elected some renowned people to head the work. It was not by chance that the soundtrack was created by Gilberto Gil. The choreography has not been performed in Brazil recently but, according to people who danced it, the show opened some doors to international stages and tournées with other choreographies of the company.

Germaine returned to Brazil some other times, but from about 2005, researchers, dancers and artists who saw the École de Sable as a possibility of improvement and getting closer with the African cultural contexts, started to do the opposite movement.

Book African Dance (Danse Africaine/ Afrikanischer Tanz), Germaine Acogny, 1980.

This flow and ongoing dialogue were mainly stimulated by the dancer and choreographer Rui Moreira, director of “Será Que? Dance company” and founder of “Rede Terreiro Contemporâneo de Dança”, who organized meetings, internships, and some training of Brazilians in the School as well as the coming of Germaine and her son Patrick Acogny for the 2006 and 2009 editions of the FAN – Festival de Arte Negra – (Black Art Festival). Rui Moreira also brought Master Longa Fo (former dancer of Mudra) and Pape Ibrahima N’diaye (dancer of Janti-Bi) for the 22nd Festival de Dança do Triângulo (Triangle dance Festival).

There is a very important movement of approaching of artists and researchers to Germaine Acogny´s work and her school and good winds for a partnership with the African continent. Displacements, changes of axes that seem to point to possibilities of finding references within our cultural contexts and increasing nets of creation and action. It´s not only to praise a movement of “return to mama Africa”, which is an old issue. These movements, already discussed in some academic researches on body issues, ancestry and legacy of the African heritage, announce a change in what we consider dance training, technical knowledge, poetry and language. Even so, changes are slow, which can be seen in the program of dance undergraduation courses in Brazil, still focused on European languages and out of step with the plurality of languages that stimulate Brazilian body.

In its chronic astigmatism, Brazil still looks in the mirror and does not see as it is.

It is necessary to know where we come from to move forward, a valuable learning from African cultures and not by chance, lesson from Germaine. At learning and absorbing it we pave the way for discovering other seas to dance and, therefore, to live.

THE RWANDA GENOCIDE One of the biggest massacres in world history, it happened in 1994, causing the death of over 800 000 people in about three months. The conflict involved two major social groups in the country, which shared the same language and many cultural habits – the majority Hutus and the minority Tutsis.The history of tension between the two groups begins with the colonial era when Belgium, the settler , established different rights in favor of the minority Tutsi over the majority Hutu, using the strategy – “divide and conquer”. The colonial authorities created identity cards stamped with the names of the groups, dividing them into opposed “ethnic groups”. Such rivalries were fueled for decades, even after the independence of the country, coming to genocide, which received little attention from the media, as well as a lack of interest and omission of international institutions, which intervened too late.

- TO READ

AFRICAN DANCE (DANSE AFRICAINE / AFRIKANISCHER TANZ)

GERMAINE ACOGNY

WEINGFARTEN 1st EDITION, 1980